True Postcards from Paradise: An Interview with Hannah Ii-Epstein Exploring Her Play, Pakalolo Sweet, & Life in the Diaspora

An Interview by Nicole Sumida

Hannah Ii-Epstein

Even today when people think of Hawai’i, white sand beaches, lush mountains and friendly, Aloha-spirited people easily come to mind. The vision of Hawai’i as a paradise free from the stressors of mainland life is firmly planted in the American psyche thanks to decades of commodified tourism. If people think of native Hawaiians at all, it is likely the image of the coconut bra and lei-wearing hula girl, swinging her hips and smiling for gleeful tourists. Most know very little about the complex history and culture of Hawai’i or what life is like for locals and Native Hawaiians today.

As a non-native Hawaiian person with island roots, I didn’t know what to expect when I saw Nothing Without a Company’s production of Not One Batu last year. Sitting in the twilight with the waves of Lake Michigan shimmering in the background, I was awed and humbled to meet Honey Girl, Ma and their crew and to be welcomed into their world as they struggled to find meaning and heal themselves. It was a revelation: to witness these fully-embodied indigenous characters tell their heartfelt stories in this city, on our shores, so far from their island home. Their words and performances were stunning.

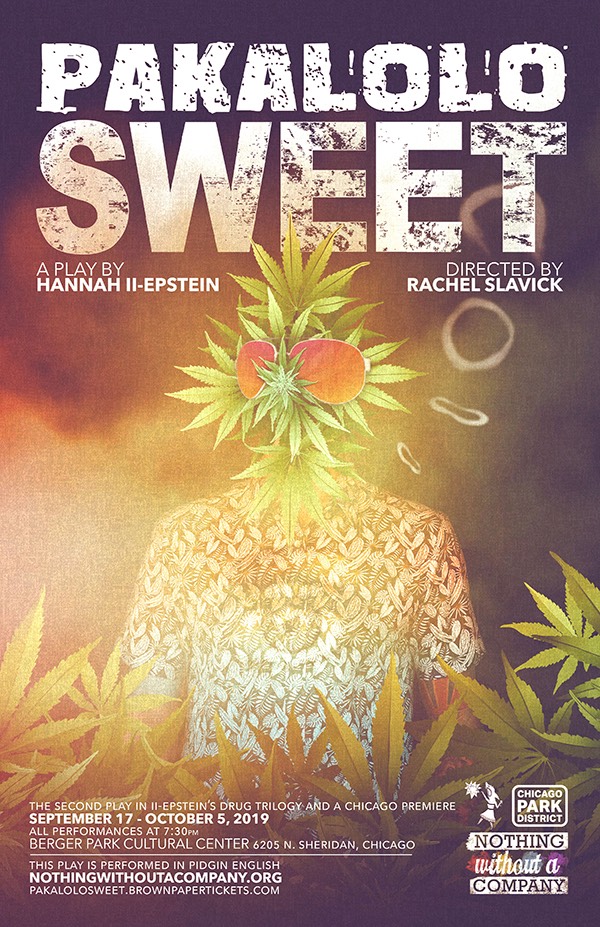

After the play, I had the honor to meet the playwright, Hannah Ii-Epstein, and learn more about her work with Nothing Without a Company, her trilogy of plays about Hawai’i and her work with the Aloha Center Chicago. Her second play in her Hawai’i trilogy, Pakalolo Sweet, will debut this week in previews (September 13, 14 & 16th), directed by Rachel Slavick with Lanialoha Lee as Cultural Specialist and Music Director. Limited run begins September 17th to October 5th, Monday through Saturday at 7:30pm and Saturday at 4:30pm in the Coach House at Berger Park Cultural Center, 6205 N. Sheridan Road, Chicago IL. Tickets available at Nothing Without a Company

Nicole Sumida: Thank you, Hannah, for taking this time to talk. I saw Not One Batu last year and was blown away. When I heard that you were staging, Pakalolo Sweet, the second play in your trilogy about life in Hawai’i, I was so excited. Can you start by sharing how you came up with the title?

Hannah Ii-Epstein: Originally, the title was called Sweet Pakalolo but then I was listening to the Not One Batu playlist, which is really my Hawai’i playlist, things from my childhood and contemporary Hawaiian music, and Humble Soul’s Pakalolo Sweet comes up. As I’m listening to it, I’m thinking “This is my play” and thought “This is perfect.” So I emailed them and asked if I could use it. They said yes so it finalized as Pakalolo Sweet.

NS: For folks who don’t know the Hawaiian language, can you share what pakalolo is and what that phrase means to you?

HI: Pakalolo is the term for cannabis that we use in Hawai’i. But the literal translation is “stupid tobacco” or “silly tobacco”. Because you smoke cannabis, you get real silly.

NS: So people in Hawai’i know and use that term, yes?

HI: Absolutely, yeah.

NS: Can you share a bit about the play?

HI: It’s about a lineage of marijuana growers, so there’s three generations of men in this family who have been growing marijuana. In Not One Batu, it was about the meth epidemic and the mother-daughter relationship, so with Pakalolo Sweet, it is about the lineage of marijuana growers but it’s also about mental health and our kane.

Pakalolo Sweet

NS: How did you get interested in this experience in Hawai’i?

HI: When I was growing up there, I was noticing how men and women were treated differently. Males had to go do the physical work. Females would stay home and do the laundry, do the dishes that type of thing. So it was super interesting to see my brother and me, and how we were treated differently. We’re a year and a half apart and I noticed how women were supposed to take care of everything and how men are supposed to put on this face of strength and masculinity. I was really interested in exploring what that meant.

NS: As you were writing it and developing the play, did you unpack things you didn’t expect to unpack?

HI: Oh yeah. It was one of these experiences where I feel plays are written differently depending on the play or playwright. With this play, I thought about for a year, year and a half to two years before I even typed anything. And then it took me three weeks, because I was in grad school at the time, to write a full first draft. During that full draft, I’m sitting and getting to the end of the play, my hands are moving and I’m not even thinking, and I start crying. Sobbing, like my pet had just died after ten years, and I’m sobbing and writing and I don’t know what’s happening cognitively. My wife walks in and she’s like, “Are you okay?!” and I was like “He had to do this…” And it was this thing, this vessel of the play taking over my body in some way. So I was writing without even thinking. It became one of those plays that you don’t really grasp what it means until an hour later. A day later. A week later. And you’re like “Whoa!” that thing that happened at the front of the play, I now know how that’s connected.

Pakalolo Sweet

NS: Is that deliberate on your part?

HI: No, no…

NS: That must be the magic of your writing. In Not One Batu, I would say the same thing. While the characters resonated with me deeply as did the space, it did take me some time to really process the depth of it, so I would say that’s the gift of your writing, to be able to impact people in that way.

HI: My director is always saying that this particular trilogy is deceptively simple. So on the surface it’s just a bunch of people, sitting around talking story, having conversations, and then it’s not until later that you figure out that as an audience member. You’re like, “Whoa!” that had an impact.

NS: Do you feel like this is your natural style of writing, something innate in you?

HI: For this trilogy, it definitely is. I’ve written other plays that didn’t come this easily or didn’t necessarily do those specific things. But because it’s the Hawai’i laid-back lifestyle and it has that front of “Cool, everything’s good”, even though underneath, nothing is good. Nothing’s ok.

NS: Not One Batu was staged at Kumu Kahua Theater in Honolulu, yes? Will you do the same with Pakalolo Sweet?

HI: Pakalolo Sweet premiered last year in September.

NS: Wow! How was that experience?!

HI: It was really cool. I love working with the Hawai’i theaters out there. They try things I’ve never thought about.

NS: So what is that process like?

HI: For Not One Batu, I was taking a class after seven years of being a playwright. I’d never taken a play writing class. I was at Columbia for fiction writing and they were like, you should take a playwriting class. So a tried it out and Carson Becker was the instructor for Playwriting 1. At the time so she shows up on the first day and writes an 808 number on the board. And I was like “Whoa!” that’s a huge sign so we start talking in pidgin and I find out that she was the literary manager for Honolulu Theatre for Youth for ten years. So she said, “Why don’t you write a play in pidgin?” I’m like, “What, you can do that?” It just never came across my mind. So I worked on Not One Batu during that class and I was going on vacation to Hawai’i and she got me in touch with Honolulu Theater for Youth because I’d never heard the play out loud in an appropriate way.

NS: With native speakers who don’t have to pretend. So how was that experience?

HI: Right. They set up little reading after their rehearsal and they invited Harry Wong, the artistic director of Kumu Kahua Theatre. So we read through the play and I got some really great notes and asked him how I can submit this to your company. He’s like, “Hannah, you’re so mainland. But you already did”. And that was it. The beginning of my relationship with Kumu Kahua. That was back in 2016.

NS: So now if you have an idea or a play…

HI: I send it over to them and ask them if they want to produce it or not. It’s super chill compared to mainland theater and submission processes. And they do five new plays a year.

NS: So that’s the plan for the third part of the trilogy? Is it written already?

HI: I just got finished with the second draft and I sent it over to Kumu Kahua. After Not One Batu, I was talking to Harry Wong and he said, “Why not make it a trilogy?” I had thought it would be one play but he propelled me into that thought. I thought if I do a trilogy about drugs in HI, with pakalolo being such a prominent drug there, and for the third one that’s called Aloha Fryday, that one will deal with hallucinogens. There’s mushrooms growing everywhere in Hawai’i. We have the angel trumpet flower, also known as bella donna, the flower that grows upside down. It grows everywhere in Hawai’i, and teenagers are like “Oh, I can get high for free, I’ll go pick that flower. “

NS: Do you do other forms of writing?

HI: I like to say I’m a creative writer and dramatist. I write everything from poetry to short fiction, long fiction, creative non-fiction, into plays, television and web series.

NS: Are you teaching writing right now?

HI: I’m a full-time writer and producer. I’m looking into work in the city colleges.

NS: Do you like teaching? Any preferences on ages of students?

HI: I love teaching. I prefer college-age because they want to be there. They’re paying money to be at this place.

NS: In the theater world, do you see a shift in the importance of representation? Is that in your mind as you write and produce?

HI: Definitely. I always have a thing on my plays that says, “This play will not be produced with an all-white cast.” or with a white cast. It’s part of my intention as a writer to make sure it’s not all white. My wife and her friends from college started this theater company, Nothing Without a Company, and I sort of came in and wasn’t sure what this theater thing is. Ike Holter, one of the founders, was like, “We need more women of color writers, so please start writing.” So we wrote my first two plays together and then Ike continued to mentor me throughout. So when I have any questions, Ike will suggest I put something in there that says so, so he gave me that intention.

NS: Can you tell me more about Nothing Without a Company? Your wife, Anna Rose, is one of the founders?

Hannah Ii-Epstein & Anna Rose Ii-Epstein of Nothing Without a Company

HI: Yes, there were five founders. While they were in college, they had a summer off and they said, “What are we going to do this summer? Let’s make a play in our house!” So that’s how the company was formed. That was in 2005. Then I joined them in 2006. Finally I was like, “Why are we spending our own money instead of other people’s money”, so we started working on the paperwork in 2007 and incorporated as a not for profit in 2008. We’ve been doing shows since then in reclaimed environments which is what I like to say.

NS: Can you say a little more about reclaimed environments?

HI: Sure, so for us, it’s environments that aren’t meant to be a theater. Part of that is for cost. We’re a small company and we can’t afford the theater fees. So we find this garage, or this park or a bar and they don’t charge so that means we can pay our actors or designers more. It’s a good thing to pay people and not things. It’s also nice to inhabit the spaces in the play.

NS: It’s such a wonderful way to create art that is accessible to people. Going back to my experience with Not One Batu, it was so powerful to watch a play about Hawai’i with the lake as the backdrop, to have the chance to really inhabit the life of the characters in that open space. You don’t get to have that experience very often. We’re always in these artificial spaces trying to imagine things.

Not One Batu

HI: The only thing we were missing was the salt water smell. I tried to bring in a mister but my director said I can’t mist the audience with salt!

NS: Love it! So you grew up in Hawai’i. On Oahu?

HI: I grew up on the north shore of Oahu. In Wailua specifically. At the time, it was a sugar cane farming town. Then eventually the sugar cane mill closed. I grew up in the height of plantation town in Hawai’i.

NS: Were your parents employed in the industry?

HI: No, my dad is from California, a haole guy who came over to be a ship boat captain and to surf. He wanted to surf every day. And my mom was a hula dancer and she ended up being an elementary school teacher for children with special needs. She got all the kalohe kids, the naughty kids. She’s a very patient person. She worked in the educational system for 30 years and they both recently retired.

NS: So when you talk to your parents now about what you’re doing or working on, especially being in the diaspora now, how do they receive it?

HI: They are very, very supportive parents all around. My dad likes to read things in advance so he was there during that first reading at Kumu Kuhua, he’s a physical presence.

NS: And your mom? Did she have a particular take on things being Native Hawaiian?

HI: She’s native Hawaiian and one fourth Chinese. She’s the youngest of 11 and our family lineage goes back to John Papa I’i, who was a teacher of the royals or ali’i. He taught everything and eventually started the Mission Houses. So if you go to Honolulu and visit the Mission Houses,that was part of his legacy. He was a writer and a teacher, and I’m finding as I do more and more research on him, I’m like Oh, this is where I’m getting it from, where I’m getting the power of my writing and why I want to connect with people and teach.

NS: Who in your family researched your family history?

HI: One of my uncles started compiling and it got lost somewhere among the 11 children and hundreds of cousins. All the first cousins are currently looking for it.

NS: For your mom, when she saw your play, did she have a perspective on it?

HI: Neither one of my parents are necessarily theater-goers, but when she saw it, I think she didn’t know her daughter had this perspective. Of course, all human stories, they make you feel things so it took her a while to say, “I feel a thing.” Like she said right away that she was proud of me, but it took her a while to say “I understand what you’re trying to do, that you’re trying to educate and bring awareness to our culture.” When we make leis, we’re talking story, we’re educating but we’re not realizing. She told me, “I’m teaching in the true Hawaiian way. Teaching in a way that people don’t know they’re learning until later.” They go, “Oh, I learned that thing!”

NS: Was your mother that sort of teacher to you?

HI: Oh, definitely.

NS: So can you tell us about other collaborations or projects you’re working on?

HI: I’m on the board of Aloha Center Chicago. We are the only Pacific Island Cultural Center in the Midwest proper, specifically learning and teaching about the Pacific Islands, not just Hawai’i but Tahiti, Samoa, all kinds of stuff. We just opened a new space this last week. I’ve had my hands full. We had Kuana Torres coming into town with a workshop. Then with Mauna Kea, we’ve been gearing a lot of energy towards what’s happening on the mountain.

NS: Could you briefly describe what’s happening on Mauna Kea?

HI: It’s been many years and I say “they” as in the government, corporations, they want to build a 30 meter telescope up on Mauna Kea. We’ve been protesting since, I think my first protest was back in 2014. We’ve been trying to stop them from building this telescope there since then. Partially because there are already 13 telescopes up there on Hawai’i proper. It’s the most sacred mountain on all of the Hawaiian islands, not only because it’s the tallest, not only because it has the only alpine fresh water source that comes from it, but it’s the closest to the gods. It’s the closest to our ancestors. That’s where my fulfillment of my protest comes from. It’s not necessarily the logistical stuff; it’s that this is where our Aloha goes. So we need to protect that.

NS: I’ve been following too, and it feels like there’s movement and I feel hopeful. While I’m not Native Hawaiian (but rather half Japanese as my mom is from Hilo), it feels like the Native Hawaiian community has become stronger because of this action. How do you feel?

HI: Now that I’ve been living on the mainland, I’ve been here over twelve years now. I’ve been here for so long and I go home to visit every 1 ½ to 2 years, but I’ve found my brain adopting to what Western or American culture is showing. My part back home hopes and my part here is about the logistics. So I’m 50/50.

NS: That makes sense. It’s hard to navigate these different mindsets. Here and there.

NS: That makes sense. It’s hard to navigate these different mindsets. Here and there.

HI: At least in halaus, we can find our space outside America, or a pocket where we can find community outside of America. This is part of the reason I can stay on the mainland because otherwise I don’t think I could live here. That’s partially why I live in Uptown, in Little Vietnam, because the grocery stores and all of the people, it’s the closest I can get to Hawai’i.

NS: It keeps that connection strong for you. I see it. It’s hard to come to the mainland and try and fit in. Some assimilate but something’s missing.

HI: Yeah, they forget a little bit.

NS: But the longing is there.

HI: That’s why the work I’m doing here is worth being here. When I look at Chicago theater or any theater, I wonder, “Is there any artistic director who is of Polynesian descent and queer?” So I gotta do the work. The purpose of being here, being a Polynesian on the mainland, I can have my relationships with the Hawai’i and Chicago theaters. It’s like getting permission from your kumu to go to the mainland. That’s how I feel Kumu Kahua Theatre is for me.

NS: So to go back to Aloha Center, you offer classes and other Polynesian art forms ?

HI: We have Tahitian, hula, Tahitian drums, ukulele, for all ages also. From keiki to kapunas.

NS: And you’re also having gatherings to support the Protect Mauna Kea movement as well?

HI: We’ll do those as needed. This Sunday is our big gathering at 7am on Foster Beach with a follow up meeting at 4pm at Aloha Center. The people on the mauna are asking for a live feed protest so we’ll show their live feed as we live feed.

NS: That is awesome. A gathering in solidarity.

HI: Yeah, people from all over the world at 11am Hawai’i time. So wherever that lands, wherever you are, you can do this.

NS: To circle back to Pakalolo Sweet, can you tell me about the run?

HI: It’s going to be at Berger Park Cultural Center Coach House. Previews are September 13, 14, 16 then we have shows from September 17 through October 5. Mondays through Saturdays at 7:30pm.

NS: Will you stage the two plays again?

HI: I’ve been submitting them around the country so hopefully someone will pick them up.

NS: What’s the plan for the rest of the year?

HI: We’ve been working with Night Out in the Parks with performances, then we’ll take Nov/Dec/Jan off and start back up in the spring.

HI: We’ve been working with Night Out in the Parks with performances, then we’ll take Nov/Dec/Jan off and start back up in the spring.

NS: When you think of both Not One Batu and Pakalolo Sweet, what do you hope the audience will come away with after seeing your plays?

HI: I think for the entire trilogy, or anything I write about Hawai’i, is for the audience to make their own postcard. When they think of Hawai’i, they think of that vintage postcard, so pretty, got the mountain, the hula lady, all those things, but we want to erase that. This is what I saw of Hawai’i when I was there and if you can’t make it there, you can make it to my play. Let’s break down those borders and let’s talk about what Hawai’i is, not what you think it is.

NS: That’s so important. I’m amazed at how persistent the stereotypical perceptions are. It’s so embedded in the American mind. No one wants to hear about the problems, what it’s like to really live in Hawai’i.

HI: Part of what we do with our plays is our one hour immersive party. People in Chicago don’t know what Hawai’i pidgin is, they don’t understand what Hawai’i is, so we give them an hour immersive party. For Pakalolo Sweet, we’re going to have a karaoke party, because there’s karaoke throughout the play. They can sing if they want or not, it can be the active listening member, like me, I don’t necessarily sing but I can cheer everyone on. It’s a way for everyone to learn to hear pidgin. They start picking it up because the actors are there. They are in character, talking to people, saying, “Do you need a juice?”

NS: Creating this experience for people, it’s such an interesting idea.

HI: The way I think about the Hawai’i pidgin language, especially to our audiences, it’s like Shakespeare. The way there’s a rhythm. Once you pick up the rhythm, you start understanding words you’ve never heard before, because it’s the intention behind that. So it’s good way for audiences to be immersed in that language and all of a sudden when the play starts, they’re like “I get what’s happening here!”

NS: Do you know Lee Tonouchi? I met him long ago at a conference, then in Honolulu, and we later published him in Riksha. He’s so great.

HI: The last time we were in Honolulu, Anna and I did a 24 hour play festival with Kumu Kahua and Lee was one of our writers. We did six brand new plays and put them out in a 24 hour period.

HI: The last time we were in Honolulu, Anna and I did a 24 hour play festival with Kumu Kahua and Lee was one of our writers. We did six brand new plays and put them out in a 24 hour period.

NS: Wow!

HI: Yeah, it was a lot of fun! Lee’s play knocked it out of the park. There were no winners but he was the winner.

NS: That’s amazing! Finally, is there anything else you’d like to share?

HI: If you’re interested in the Pacific Islands, come to the play. That’s a good place to start. Come to Aloha Center, come check us out. Nothing Without a Company and Aloha Center are in a partnership, for this trilogy of plays we’re doing, and part of it is having Lanialoha Lee, who is our cultural specialist, which means she talks with the cast about what is up with our culture, what is appropriate and what is appropriation. In Chicago theater, we’re starting to have intimacy choreographers, designers and we’re beginning to understand how our actors are being treated, especially with the Me Too movement. We hope specialists become a staple in Chicago theatre. If we’re doing a play about a culture, we should probably have someone from that culture there to talk about their experience.

NS: Is that a trend you’re seeing?

HI: I want to start that trend.

NS: Right on. Thank you so much, Hannah, for making time to talk with me. Congratulations & can’t wait to see Pakalolo Sweet!

HI: Thank you!

End.

About the Writer/Dramatist

Hannah Ii-Epstein (she/her/hers), born and raised on the North Shore of Oahu, recently received her MFA in Writing for the Screen + Stage at Northwestern University. In 2015 Hannah graduated summa cum laude with a B.A in Fiction Writing at Columbia College Chicago. She is a writer of fiction, poetry, screenplays, plays, and musicals. She is a member of the Hawaiian Civic Club and Aloha Center Chicago. She is a Co-Artistic Director, Board Member, and Founding Member of Nothing Without a Company. Since 2007, over ten of her plays and musicals have been produced in Hawaii and Chicago by Kumu Kahua Theatre, Nothing Without a Company, About Face Theatre’s Babes on Stage, Fury Theatre’s SAST, Mary-Archie’s Abbie Fest, and Nothing Special Production’s Fight Night. Hannah has participated as a writer in many 24 Hour Fests for Nothing Without a Company, Silent Theatre, Columbia College Chicago, and Northwestern University. She was awarded 30 under 30 in Windy City Times in 2014. Hannah’s film, Sweet, won Best Film Runner Up in Chicago’s 48 Hour Film Project in 2015. In 2016 Hannah and her play, Not One Batu, was honored by Hawai’i State Theatre Council Po’okela Awards in the categories of Non-Resident Guest Artist and Overall Play. In 2018. Not One Batu was Jeff and Reader Recommended in Chicago IL. Hannah Ii-Epstein

Nothing Without a Company is producing innovative, thought provoking, and quality art; encouraging our audiences to think outside of the box. We seek to maintain financial sustainability and to create job opportunities in Chicago’s diverse art community. Nothing Without a Company especially supports LGBTQIA artists by providing a safe and creative space to explore their voices and talents. We encourage emerging artists by hosting live panels, creative mentorship opportunities, and exclusive workshops and programs to develop site-specific and immersive theatre. Nothing Without a Company

For more information about the Aloha Center Chicago, contact them via Facebook or by email: alohacenterchicago@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

+ There are no comments

Add yours