What We Feed Ourselves

by Cori Nakamura Lin and Jami Nakamura Lin

During quarantine, many of us are eating at home much more often than before. Whether this means physically eating in our home versus prepping food to take to work, or cooking for ourselves instead of going out to eat, our home-food-scape has changed drastically. In quarantine, I have struggled to put care and love into feeding myself the way that comes easily to me when feeding or sharing food with others. I hope that, while in the chaos of a global pandemic, we can treasure the foods that make us feel safe and cared for, and give ourselves a little bit of love in the ways we feed ourselves. -cori

[Adapted from the What We Feed Ourselves: Food, Culture, and Acculturation book & art project we completed in the Twin Cities in 2019. WWFO was funded by the Minnesota State Arts Board, Metro Regional Arts Council, and Great Streets Fund. For more on the project, check out our website.]

Growing up in the Chicago suburbs, our young Asian American identities were formed primarily in contrast to whiteness. We learned what (white) Americans thought of Asian cuisine before we grasped what Taiwanese and Japanese foods meant to us personally. For example: we internalized the idea that “Chinese” food was unhealthy and cheap, avoiding the deliciousness of dim sum, duck, and dou jiang for years. We were like that little kitten, Yoko, in the eponymous children’s book by Rosemary Wells— the one who is embarrassed that no one wants to eat her “crab cones” (temaki, in a horrifying translation) or try her red bean ice cream.

With little cultural and political representation in the United States, recent immigrant cultures are usually most visible through their food. Our conception of other cultures’ food is often filtered through what we are served at “ethnic restaurants,” without an understanding of the ways that dishes and customs change when the owners need to keep their lights on.

Our larger project, What We Feed Ourselves, is not a response to cultural appropriation but a redirection. Before we can talk about authenticity, we need to understand what exactly we are honoring as authentic. Our goal is not to create or support a black-and-white dichotomy between these home foods (what we feed ourselves) and restaurant foods (what we feed others). We do not want to call one true and the other false. Instead, WWFO attempts to investigate and interrogate the ways food changes, based on the path it takes, based on whose tastes (and spice tolerances!) we are entertaining, and based on who is controlling the narrative and translation. (For example, the Chinese street food jianbing (a crispy fried batter topped with savory sauces, meats, and other condiments, then folded) is usually translated in America as “Chinese crepe.” This translation assumes a familiarity with crepes— a French food— and uses the dominant European cuisine as the baseline.)

We want to honor migrants and their reasons for migration. We want to acknowledge cultural change–both natural and forced. We want to appreciate the trade-offs we make when we feed others, and recognize the soul-filling satisfaction when we feed ourselves.

Here are some of our homefoods:

Ikura musubi

(Rice ball filled with salmon and salmon roe and wrapped in nori)

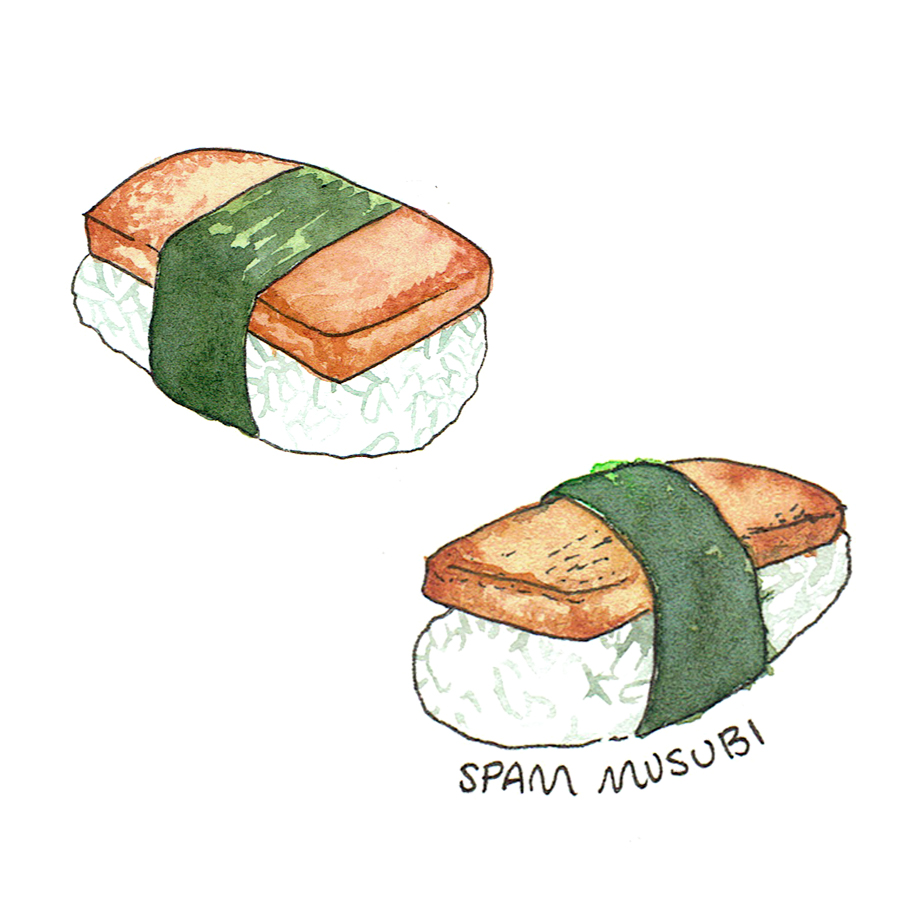

Spam musubi

(Rice ball with Spam fried with a shoyu sauce and wrapped in nori. In our family, we called both of these types musubi

Dou Jiang, You Tiao

(Taiwanese fresh sweetened soy milk and fried dough cruller)

Congee

(In our family, we always called this soupy rice.)

About the Artist/Author

Cori Nakamura Lin is a Japanese//Taiwanese-American illustrator and designer based in Chicago, IL and Minneapolis, MN. By visualizing narratives and illuminating concepts, she make art that fuels action. Her work has been published in the LA Times, Twin Cities Daily Planet, and Pollen Midwest.

Cori enjoys working with people who love food, people who have a mission, and those with a tale to tell. In all of her work, she focuses on the stories of people of color and other marginalized people, bringing their experiences to the center. To learn more: Cori Lin

About the Author

Jami Nakamura Lin is a Japanese Taiwanese American writer and reader based outside Chicago. She writes about mythology and memory and culture and mind. Her essays and stories appear or are forthcoming in publications like Catapult, Electric Literature, Library Journal, Passages North, PANK, and more. Her work was recently featured in the anthology What God is Honored Here? (University of Minnesota Press, 2019). Jami received a Creative Artists’ Fellowship from the Japan-US Friendship Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts in 2016 and an inaugural Walter Dean Myers Award from We Need Diverse Books in 2015.

With her sister, Cori Lin, Jami runs ROKUROKUBI, on ongoing visual narrative project. To learn more: Jami Nakamura Lin

You must be logged in to post a comment.

+ There are no comments

Add yours